The post Van’s Aircraft Issues RV-12 Service Bulletin Following Fatal Crash appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>Van’s said it issued a service bulletin requiring the action Monday “out of an abundance of caution” following a fatal RV-12 crash earlier this month after it appeared that the control stick on the pilot’s side disconnected while in flight due to improper assembly.

The aircraft was a homebuilt aircraft and the pilot was the builder.

The release of Service Bulletin 000102 comes as the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) released its preliminary findings of the June 6 accident where an RV-12 pilot lost control authority and crashed during an attempt to land at Auburn Municipal Airport (S50) south of Seattle.

According to FAA records, the aircraft received its airworthiness certificate in May 2021.

READ MORE: Van’s Aircraft, 50 Years in the Making

According to the NTSB report (below), the pilot was on a VFR pleasure flight and intended to land at Auburn airport, a nontowered facility with several flight schools. The pilot overflew the airport from the east and announced over the CTAF that he intended to enter left traffic for Runway 35, which put him on the west side of the facility.

The ADS-B data indicates that in the 60 seconds after making the transmission, the airplane entered a descent from 1,500 feet to 1,250 feet. As it rolled on to the left downwind, the pilot transmitted, “Pan Pan RV412JN, I just had a control failure, I’m inbound for 35, without any controls.”

Multiple pilots who were witnesses to the accident told NTSB investigators that the airplane began a descending turn to the left described as “a spin or spiral dive.”

The aircraft came down in an industrial park less than a mile from the threshold of Runway 35, crashing through the roof of an occupied warehouse.

A security camera captured the final three seconds of the flight, showing the airplane in a descending left turn. The aircraft was inverted and in a 45-degree nose-down attitude as it went through the building, killing the pilot.

There was no fire, and no one in the warehouse was injured, although they were momentarily trapped as the wreckage blocked their egress into the reception area of the building. Video of the accident scene by local television stations showed wreckage and fuel spilled inside the building and fragments of the aircraft’s left wing on the roof.

According to the NTSB, the forward cabin of the aircraft sustained crush damage through to the main wing spar. The complete right and the inboard left section of the wings remained attached to the fuselage by the main spar.

READ MORE: The Evolution of Van’s Aircraft

The aircraft’s roll control system consisted of full-length flaperons connected to tandem control sticks through a series of pushrods, torque tubes, and a centrally mounted flaperon mixer bellcrank. Examination of the wreckage revealed that the left control stick pushrod was not connected to the inboard eye bolt bearing at the flaperon mixer bellcrank.

The preliminary investigation included reviewing the plans for the aircraft, which determined that the inboard eye bolts on the accident airplane were installed upside down, which allowed the stud end of the eye bolt to rotate within the threaded inboard section of the pushrod until the left control stick had become disconnected.

Investigators determined that the airframe had approximately 100 hours on it at the time of the accident.

The final report from the NTSB will be released at the conclusion of the investigation, which is expected to conclude in 18 to 24 months.

The post Van’s Aircraft Issues RV-12 Service Bulletin Following Fatal Crash appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post New Timeline Projected for MOSAIC Final Rule appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>When the comment period closed for the MOSAIC Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) in January, it was suggested that the final rule might be announced at EAA AirVenture in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, in late July, but that is no longer the expectation.

“It is correct that early to mid-2025 is expected to be the announcement of the final rule,” said EAA spokesman Dick Knapinski. “That’s been no secret. We’ve been telling those who ask that, based on our conversations with the FAA, most recently at our annual winter summit in Oshkosh in early March.”

Knapinski said the FAA sincerely wanted to get the rule ready for this year’s AirVenture, “but it would have been an impressive stretch even in the best of circumstances, given that the NPRM public comment period closed in early 2024. Any slippage would have made that even tougher.”

The timeline was also hit by the need to reopen comments for 30 days in February to backfill an omission in the original document.

The coming election will also use government resources that would be needed to process the new rule, which is intended to reduce certification burdens for new and legacy recreational aircraft while enhancing safety with new technology. Knapinski said the Department of Transportation will release its spring rulemaking plans in a few weeks, and that should give an official timeline for the MOSAIC rule.

Editor’s Note: This article first appeared on AVweb.

The post New Timeline Projected for MOSAIC Final Rule appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post FAA’s MOSAIC Comment Window Is Soon Closing appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>Recreational flying fans: I don’t know about you, but I’m getting pretty tired of studying MOSAIC [FAA’s Modernization of Special Airworthiness Certification proposed regulation]. It’s been on my mind every day since the FAA issued it on July 24 just before EAA AirVenture Oshkosh started.

I’ve studied this pretty closely—thanks so much to Roy Beisswenger, founder and proprietor of Easy Flight, for his effort to make a study guide. This is not an easy read, but it has much we want plus a few things we question or want changed.

If you want some part changed, you have to comment. I can comment and many others have. That’s good, but the FAA needs a loud response. With 39 days left at posting time, 389 pilots have commented. Your comment is still needed.

The FAA’s comment period for the MOSAIC Notice of Proposed Rule Making (NPRM) will close on October 23.

A series of master class videos on MOSAIC may be found here.

To ensure my facts were as accurate as possible, I consulted several other experts, each focused on specific areas of interest.

Linked with my own experience — serving on the ASTM committee for many years, going to visit the FAA in its government offices in Washington, D.C. (several times), and discussions with the Light Aircraft Manufacturers Association (LAMA) board, plus numerous other aviation leaders—the video below provides the best information I can offer at this time.

Is it a perfect understanding of all things MOSAIC? No, I keep uncovering new tidbits buried in this lengthy document. Others have often pointed out things I missed.

The video below provides as much detail as possible as quickly as possible in a form not too difficult to consume. It also draws attention to areas where people have found problems or have unresolved issues with what is presented. The video tries to illustrate these simply and clearly. I hope you’ll have a look.

Where Are the Comments?

If you get through all 45 minutes of the video presentation below, you will discover that the Q&A portion does not appear. This portion of our discussions went on nearly as long as the formal presentation. It simply got too long and took too much editing.

I was fascinated when during Q&A discussions erupted on their own. Being particularly passionate about a part of MOSAIC and our privilege to fly, attendees often spoke to one another without my input. This was invigorating to witness, but it was sometimes challenging to hear what people said, and not in every case could I keep up with the conversations. In short, I think you’d find it less useful than what I will present.

I am going through all of those comments carefully and will summarize them in printed form, which I think will be much easier to consume.

While I work on that, I encourage you to do what the video suggests: Go up to the search bar at the top of this page and type in MOSAIC. That will bring up everything I’ve written about the NPRM in chronological order. A few articles on Mosaic Light Sport Aircraft will be sprinkled among rule-oriented articles, but all have some useful information.

A few of those articles generated lots of comments. In fact, at the time I gave these two talks, this website had generated more total comments than the FAA’s website—a fact I hope will change dramatically in a new direction soon. I know people tend to wait until toward the end to act, but pilots shouldn’t cut the deadline too close.

If the FAA’s new rules are important to you, I urge you to watch this video.

Helpful Links

- USUA/LAMA MOSAIC NPRM study guide, download a PDF document with bookmarks and helpful organization

- A MOSAIC study guide

- Make a comment, direct link to FAA’s comment page

- Read what other commenters have said, FAA comment page

The post FAA’s MOSAIC Comment Window Is Soon Closing appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post Direct Fly’s Alto NG a Beautiful Bargain appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>At Midwest LSA Expo day two, I gave my first talk about the FAA’s Modernization of Special Airworthiness Certification (MOSAIC ) regulation rulemaking to an SRO room. The video turned out well, so following some editing on the Q&A session that followed, I pledge to get this up next week.

My presentation was a distillation of 318 original pages into a 45-minute presentation. Some described it as “drinking out of a fire hose.” The question and answer session added 30 minutes. Pilots in the audience helped me better understand this MOSAIC monster. I hoped that would happen, and I’m pleased it did.

After going through the entire document twice and multiple times for some portions, more is yet to be discovered (though I’m getting weary of studying it).

Beyond MOSAIC

After a vigorous discussion about the FAA’s new rule, I was keen to get outside among the airplanes I enjoy. In particular, I wanted to get a closer look at Direct Fly’s Alto NG. This is not an entirely new airplane to Americans—we’ve seen Alto 100—but the brand suffered from ineffective representation and was in danger of fading from the scene in the U.S.

In swooped Ken McConnaughhay from Searcy, Arkansas, on the same airfield as longtime Aeroprakt importer Dennis Long. Long has been assisting McConnaughhay as he takes over importing, sales, and service of Alto NGs.

McConnaughhay is a multitalented pilot who has done crop dusting for many years and flies a King Air 350 as a corporate pilot. He admits that the light weight of Alto NG was a learning experience, but he is very impressed with the machine.

While I’d say Alto NG is a bargain, that’s one of those loaded phrases like “affordable.” So let’s state right up front that as equipped as seen in the pictures accompanying this article, Alto NG sells for $147,500.

Finding that price affordable is a subjective evaluation. You buy what you can afford, of course. Yet an aircraft that looks this way and costs $147,500 in 2023 could be compared to perhaps $120,000 only a few years ago. You know everything costs more today than it did in 2018.

Airplanes are no different. Producers have been tossed around by inflation, supply chain challenges, shortages of materials and labor, war, and increasing regulation, along with many other expenses that are troubling all kinds of businesses.

That explanation may not help you afford Alto NG, but $147,500 for a handsome, well-equipped aircraft with a large Dynon SkyView, Dynon radios, ADSB in and out, and Dynon autopilot is fairly priced in today’s market. Alto NG comes standard with the Rotax 912 ULS, and a three-blade Kiev ground-adjustable composite prop.

The interior was color-matched by Direct Fly to coordinate with the exterior paint scheme. Clearly, Direct Fly is accomplished at painting and other finish work. The closer you look at this airplane the more you notice the details.

When I asked McConnaughhay to describe some of the performance criteria of the airplane, he summarized: “It’s not the fastest airplane in the LSA fleet, but neither is it the slowest.” He related that he commonly flies at altitudes of around 7,000-8,000 feet, and at that altitude he will see 108 knot cruise from his power setting of 5,000 rpm, and he reported burning about 6 gallons per hour. Long advised McConnaughhay that operating at 4,700 or 4,800 rpm brings burn rates closer to 4 gallons per hour.

“The advantages of Alto lie in its simple and comfortable piloting, which is guaranteed by the design of the wing” Direct Fly said. “The rectangular wing plan and the profile with a blunt leading edge provide predictable stall characteristics and behavior.”

“It’s suitable for a beginner pilot because of its gentle flight qualities,” McConnaughhay added. “However, I’m proof that it’s also satisfying to an experienced corporate pilot.”

With good looks and a beautiful finish, benign and satisfying flight characteristics, and what must be described as a fair price tag in 2023, I suspect we will see more Direct Fly Alto NGs in the future.

Why wait two years for a MOSAIC aircraft of your dreams (which will probably come at a significantly higher price), when you can have this beauty today? If you’d been at Midwest LSA Expo, you could’ve bought this handsome airplane and flown it home.

Technical Specifications

Direct Fly Alto NG (All information supplied by the manufacturer)

- Length: 21 feet

- Height: 7.4 feet

- Wingspan: 26.9 feet

- Wing area: 114 square feet

- Cockpit width: 43.3 inches

- Fuel tank capacity: 24.3 gallons

- Powerplant: Rotax 912ULS

- Take-off distance over a 50 foot obstacle: 1,345 feet

- Landing distance over a 50 foot obstacle: 968 feet

- Empty weight: 705 pounds

- Maximum takeoff weight: 1,320 pounds

- Never Exceed Speed: 140 knots

- Cruising speed: 97 knots (Ken commonly achieves 108 knots at 5,000 RPM)

- Stalling speed, landing configuration: 41 knots

- Stalling speed, clean configuration: 47 knots

- Load factor: +4/-2

- Maximum Climb Speed: 1,000 feet per minute

The post Direct Fly’s Alto NG a Beautiful Bargain appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post Van’s Updates List of RV Parts Reportedly Forming Cracks appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>Van’s published a notice about the problem and followed with a live update last week at EAA AirVenture, reported KITPLANES.

The cracks affected certain parts with rivet holes that need to be dimpled for flush riveting during assembly. The company said the defects resulted from changes in the process of laser-cutting parts. During the period from February 2022 through June , Van’s had an outside vendor produce the parts with laser-cut rivet holes instead of using the traditional press-punch method employed previously.

Van’s said the change was meant to boost production and relieve a backlog affecting kit deliveries. Company president and chief engineer Rian Johnson said the company’s thinner parts were outsourced for the laser cutting and most were in noncritical parts of the airframe. According to Van’s, it has discontinued the use of laser-cut parts and has acquired a new, larger press-punch machine.

Apparently the cutting of rivet holes resulted in overheating of the metal in certain places, Van’s said. Builders reported the defects, including cracks that appeared after the holes were dimpled.

During his AirVenture presentation in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, Johnson described the testing taking place at the factory to address the defects. The company has told customers to stop building with the laser-cut parts for now, and Johnson asked them to be patient for the estimated 45- to 60-day period Van’s will need to finish testing.

The bottom line for builders of the affected kits is that while some parts will be acceptable for low-stress applications, others will have to be replaced. Van’s said it is setting up a process for providing customers with replacement parts.

The post Van’s Updates List of RV Parts Reportedly Forming Cracks appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post CubCrafters Unveils Carbon Cub UL appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The Carbon Cub was first introduced in 2009 and quickly became a favorite of the backcountry aviation set. The newest Cub variant made by the Yakima, Washington-based light sport aircraft (LSA) manufacturer was also designed to capture a larger share of the European ultralight market, the company said.

The aircraft is also the first to be powered by the Rotax 916iS engine.

The aircraft on display at Sun ‘n Fun was flown across the country to the airshow by Brad Damm, CubCrafter’s vice president of sales and marketing. Prior to the journey, Damm—an accomplished pilot—primarily had experience flying CubCrafter aircraft powered by Lycoming engines.

“It was my first real experience behind the Rotax, and now I am part of their big fan club,” he said. “The Rotax 916iS is a 160 hp turbocharged engine. It can handle density altitude. It can make takeoff power up to 17,000 feet.”

Damm carried supplemental oxygen on the trip, allowing him to safely climb up to 17,500 feet.

“My true airspeed was 150 mph. I had a nice tailwind, so my ground speed was showing as 230 mph.”

The trip to Florida is a warm-up before the intensive aircraft testing begins. When the airplane gets back to Washington, it will be put through rigorous testing to fine-tune the design.

“I’d say you are looking at 70 percent of what to expect,” Damm said, adding that testing is expected to be completed by 2023, with deliveries to follow in early 2025.

About the Airplane

The Carbon Cub UL was made possible through a collaboration of CubCrafters and BRP-Rotax, the makers of its new 160 hp turbocharged engine. The engine manufacturer makes two- and four-stroke engines that power everything from sport aircraft and snowmobiles to watercraft.

CubCrafters said the aircraft reflects their goal of creating a new airplane that features multi-fuel technology (mogas and avgas) and fully meets (American Society for Testing and Materials) ASTM standards while carrying two adults with a full fuel load and a reasonable amount of baggage at a takeoff weight of 600 kg (1,320 pounds).

“The new 916iS engine is lighter, more fuel efficient, and can produce more power than the normally aspirated CC340 engine on the Carbon Cub SS in higher density altitude scenarios,” Damm said.

The Carbon Cub UL has full authority digital engine control (FADEC). “There is no mixture,” Damm explained. “A computer monitors the engine, which makes it very efficient. Instead of burning 12 gallons an hour, it burns closer to eight or nine.”

While the production version of the latest aircraft is slated to be initially built, certified, and test flown as a LSA, it will also meet ultralight category requirements in many international jurisdictions, according to the company.

“The aircraft can remain in the LSA category for our customers in Australia, New Zealand, Israel, and even the United States, but it can also be deregistered, exported, and then re-registered as an ultralight category aircraft in many jurisdictions in Europe, South America, and elsewhere,” Damm said. “Our kit aircraft program has always been strong in overseas markets, and now we are very excited to have a fully factory-assembled and tested aircraft to offer to our international customers.”

The post CubCrafters Unveils Carbon Cub UL appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post The Increasingly Rare Pleasure of the Beechcraft Skipper appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>

In terms of outward appearance, the Piper PA-38 Tomahawk and Beechcraft Skipper look nearly identical. The visual differences are few and minor, and differentiating them requires some attention to detail. The Tomahawk has square side windows and a full wraparound rear window, for example, while the Skipper has trapezoidal side windows and two separate triangular rear windows.

The Tomahawk’s vertical stabilizer extends above the horizontal stabilizer while the Skipper’s is a true T-tail, resembling that of its big brother, the Beechcraft King Air. This was intentional on Beechcraft’s part; in print ads, the Skipper was touted as using “the T-tail design of the Super King Air turboprop.” And while theTomahawk’s gear attaches at the wing, the Skipper’s is slightly narrower and attaches to the fuselage’s belly.

Beyond those differences, the two models are near carbon copies in terms of appearance. While the competitive environment in those days was rather cut-throat and corporate espionage has been suggested as the reason for the similarity, inherent technical constraints likely played a large part.

Tasked with utilizing the same power plant (the 112-to 115-hp Lycoming O-235), carrying two people, and offering comfort and visibility superior to the Cessna 150 in a low-wing configuration, it’s perhaps not surprising that both Piper and Beechcraft arrived at the same general layout when designing their new trainers.

In the case of the Skipper, the design goals seem to have been achieved. Cabin space is noticeably more accommodating than the 150/152, and outward visibility is similarly superior by virtue of the low wing and large windows.

Overall, the Skipper’s cabin indeed feels like a more ergonomic, pleasant place to be when compared with the 150/152.

Model History

Unlike other types that were produced over many decades and were offered in dozens of subtypes, the Skipper is simple and uniform. Only the Model 77 was produced, with no special editions or improved versions ever offered. Accordingly, Skippers are consistent in specifications, amenities, and stock panel layouts.

The prototype first flew in 1975, two years after the Tomahawk’s first flight. After lengthy experimentation with various engines and tail configurations, production started in 1979. Beechcraft built a total of 312 Skipper examples through 1981.

At that time, the market began to soften and Beechcraft suspended production, reportedly pending an improvement in market conditions. No such improvement occurred, however, and some unsold Skippers were offered as 1982 models.

Market Snapshot

When it comes to assessing the current market value of the Skipper, its rarity makes it more challenging to evaluate than others. Combing through the offerings of over a half-dozen sources for three months, we were only able to find six examples listed for sale. This includes regular scouring of Craigslists nationwide as well as eBay. Few Skippers were built to begin with, fewer remain today, and naturally, only a handful are listed for sale each year.

Of the examples we found, the least expensive was listed for $30,000 and the most expensive was listed for $45,000. The median price came to $34,000, and the median total airframe time was 4,900 hours. Among 1980s-era aircraft, it’s one of the most affordable.

Flight Characteristics

The Skipper stands out on most ramps. A relatively unique design compared with traditional Cessnas and Pipers, the Skipper’s larger and taller cabin creates greater ramp presence than a 150 or 152, as does he T-tail. When it’s time for the preflight, the T-tail becomes more of a nuisance than a benefit, as close inspection and snow/ice removal are far more cumbersome than with a conventional low horizontal stabilizer.

With a cabin that places the seat 7 inches higher than the 150’s, boarding the Skipper feels quite a bit different. Rather than ducking beneath an eye-level wing to enter a relatively claustrophobic cabin, one climbs up onto the Skipper’s wing and steps through a comparatively massive, welcoming door.

After settling into the seat that’s perched atop the low wing, the outward view is open and bright. Headroom and shoulder room are ample, and with 5 additional inches of cabin width compared to the 150, husky occupants needn’t inhale deeply to shut the doors. This additional space also allows occupants to wear multiple layers and winter coats without feeling too cramped.

Beechcraft engineers began with a clean sheet when designing the cabin and panel, and accordingly, the ergonomics are outstanding. The panel is clean and uncluttered, the circuit breakers and radios are all positioned above the level of the yokes, and the engine instruments are intuitively organized immediately above the throttle and mixture levers.

Stepping on the brakes and handling the controls, it becomes evident that those same engineers wanted to make the diminutive Skipper feel like a larger Beechcraft. The yokes are substantial and exhibit none of the flex inherent in the Tomahawk and 150. The rudder pedals are large aluminum affairs, solid and beefy. And most of the touchpoints are similarly reinforced to provide an overall feeling of quality compared with other bargain-basement types.

Performance-wise, the most limiting aspect of theSkipper is the meager useful load. With 30 gallons of fuel capacity, the full-fuel payload is only 400 pounds. With the addition of optional avionics and typical cabin items, a Skipper pilot must be vigilant about passenger weights and may consider leaving some fuel behind for shorter flights.

With 115 hp on tap, the reality of always operating within a few hundred pounds of maximum takeoff weight makes for a relatively lazy takeoff roll and half-hearted climb performance. The book claims a climb rate of 700 fpm is achievable at gross weight, but as with many types, an aging engine and airframe make such numbers appear rather optimistic in reality. Taking off and climbing are not what it does best.

After leveling off, the Skipper can cruise at 105 knots at 2,700 rpm and about 95 knots at 2,450 rpm, numbers on par with many other two-place aircraft in the 100-hp range.

In flight, the Skipper is defined not by any particular performance number, but rather by the quiet competence with which it handles. The solid-feeling controls are smooth and effective, relaying a feeling of robust quality. Handling is entirely predictable and unremarkable, with no unusual traits or characteristics. One simply asks the Skipper to pitch, bank, or stall, and the airplane does as expected without comment or complaint.

Regard the T-tail with some caution, as it has the propensity to act differently during takeoff and landing than conventional tails mounted lower on the empennage. That said, the effect was less noticeable in the example we flew compared with the Tomahawk. Once again, the Skipper generally does as asked with-out complaint.

Ownership

Without question, the single most challenging as-pect of Skipper ownership is the rarity of the type. With such a small fleet size, airframe parts can be difficult to source, qualified and experienced instructors can be hard to find, and support from other owners is not nearly as robust or commonplace as with other types.

The problem is significant, and it’s not getting better. In 1982, most if not all of the 312 examples built were flying. Twenty years later, reports offered that roughly 210 Skippers were active on the FAA register. Today, after another 20 years have passed, only 118 examples appear on the register. If this trend continues, the Skipper will be virtually extinct by 2042.

Accordingly, a prospective Skipper owner must be willing to become a parts-sourcing enthusiast, seeking out and procuring parts before they’re needed. This may involve saving keyword searches on eBay to receive notifications when parts are listed and monitoring salvage websites for wrecked Skippers from which parts can be taken.

There’s a fine line between stockpiling and hoarding, however. To serve as a responsible steward of the type, one should engage with other owners and be willing to sell or exchange spare parts as needed. Making spare parts available to the entire owner group helps to keep the remaining Skippers airworthy and flying, and establishing such goodwill also helps to ensure you will be able to find and obtain parts in your own time of need.

With a 2,400-hour engine TBO and a fuel burn of 6 to 8 gph, ongoing operating expenses are minimal and so are the insurance premiums. One owner reported that with a $25,000 hull value, the annual premium to cover a zero-time pilot was $1,100. This year, when the policy was adjusted to a $35,000 hull value and all covered pilots had more advanced ratings, the annual premium dropped to $700.

Perhaps because so few Skipperswere produced, few airworthiness directives (ADs) apply to the airframe. Of the 11 applicable ADs listed on the FAA database, only one involves a repetitive inspection. It’s fairly straight-forward in nature, requiring a dye penetrant inspection of the nosegear fork axle assembly every 500 hours, and a visual inspection of the assembly every subsequent 100 hours.

Although some 165 supplemental type certificates (STCs) are approved for the Skipper, most are relatively minor. With the exception of those that modernize the panel and avionics, few will have an appreciable effect on the value of an individual airplane. Nor will any of the approved STCs increase horsepower or performance as the vast majority are related to instrumentation, LED lighting, oil filters, and ADS-B installations. Accordingly, most Skippers are largely unchanged from their factory configuration today.

The Beech Aero Club is the official type club of the Skipper. A well-organized and vibrant group, it serves as a source for technical documents and forums in which owners can ask for and provide advice. Like the aircraft itself, however, Skipper owners are correspondingly fewer than owners of other types, and even within the type club, some effort is required to locate experienced owners and maintainers.

The Skipper is one of the few ways to obtain a well-refined, nicely-flying, 1980s-era aircraft in the mid-$30,000 range. The low price of entry reflects the scarcity of airframe parts and type expertise. But with a popular, commonly-found engine and the ever-increasing reach of online networking, the Skipper’s most significant weakness can be manageable with appropriately-adjusted expectations.

In the end, a well-maintained Skipper will likely serve as an enjoyable personal airplane for decades to come.

BEECHCRAFT SKIPPER

Price: $30,000 to $45,000

Powerplant (original): Lycoming 0-235, 115 HP Max Cruise

Speed: 105 mph

Endurance: 4.9 hours

Max Useful Load: 580 lbs.

Takeoff Distance Over a 50-ft. Obstacle: 1,350 ft.

Landing Distance Over a 50-ft. Obstacle: 1,300 feet ft.

Insurance Cost: Low

Annual Inspection Expense: Low

Recurring ADs: One Minor

Parts Availability: Poor

Stalls are Very Adequate for Teaching Purposes

Beechcraft took nearly six years to develop its new trainer, the Skipper, using the GAW-1 airfoil that Cessna had initially tapped for the Model 303 Crusader. The result was a stately if unexciting ride that the company promoted extensively in FLYING’s pages in the early 1980s. Beech tested the airplane with both a conventional tail as well as the T-tail it eventually delivered with. In the September 1979 issue, Richard Collins described flying the new take on training aircraft.

“A Beech design goal for the Skipper was to develop an airplane that would stall cleanly and not fall off and start to spin without provocation. The airplane is approved for spins, but Beech wanted it to spin only when the pilot demanded it, not accidentally, at the drop of a wing.

“Their goals have been met. Aerodynamic warning of a stall is good, without an excessive amount of tail buffeting. The Skipper also has what must be one of the world’s loudest stall-warning horns. The airplane can be held in a stall without tending toward an instant spin; while it is stalled, you can hold the wings level by using ailerons alone and not provoke the airplane. The stalls are very adequate for teaching purposes.”

The post The Increasingly Rare Pleasure of the Beechcraft Skipper appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post Piper J-3 Cub’s Heritage of Simplicity, Reliability appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>Such was the case with the Piper J-3 Cub. Devoid of an electrical system, flaps, radios, and just about anything that can be considered a creature comfort, it provided only the bare minimum necessary to function as an airplane. Fortunately, such simplicity translates to light weight and increased reliability, so when Piper presented the Cub as an ideal trainer, the formula worked very well.

As is often the case, the question of how well the Cub’s recipe of pared-down simplicity serves the needs of a new first-time buyer depends entirely on the individual’s preferences and future plans. For someone interested in longer-distance travel or load-carrying capability, it comes up short. But for someone interested in fair-weather adventuring to nearby pancake breakfasts and exploring grass strips, it just might be the perfect machine.

Here, we take a closer look at the iconic J-3 Cub and explore what it’s like to own, fly, and maintain.

Design

The J-3’s design can be traced back to the Taylor E-2 from the early 1930s. The original E-2 looked similar to the J-3, but was equipped with a 37 hp Continental A40 engine and a non-steerable tailskid—and it had no brakes.

When the Taylor Aircraft Company filed for bankruptcy in the late 1930s, William T. Piper purchased it and utilized the E-2 as the basis for the Piper J-3. The Piper design introduced more powerful engines with the 65 hp Continental becoming the most popular. Brakes and steerable tailwheels were added, and the company offered a floatplane version.

The resulting design has proven durable, and the Cub remains one of the most imitated in GA.

Model History

Although the J-3 could be considered a success in the late 1930s and into the 1940s with nearly 2,000 sold in both 1940 and 1941, much of the J-3’s success can be attributed to fortunate timing. With the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 and the U.S.’ subsequent entry into World War II, the military suddenly required a large number of light aircraft for reconnaissance, observation, and liaison duties.

Piper came through, producing several thousand examples of the L-4 Grasshopper, which was essentially a J-3 Cub with additional windows and different paint. While the sale of so many L-4s was a boon to Piper, the subsequent boom of postwar sales was even more so. At a price of $2,195 (the equivalent of just under $30,000 today), the J-3 was both affordable and appealing to soldiers returning from the war. Accordingly, Piper sold around 7,000 J-3s in 1946 alone. Ultimately, nearly 20,000 were produced between 1938 and1947, and 3,796 Piper J-3s remain active on the FAA aircraft registry today.

Market Snapshot

The market value of the Piper Cub reflects more than the sum of its parts. Compared to similar types like Taylorcrafts and Aeroncas, the Cub’s historical significance and cachet elevates its value substantially. For a buyer only interested in an airplane’s performance and utility, other types that aren’t as sought after will likely provide better value. But for a buyer that is enchanted by the Cub’s legacy, there is no substitute.

A recent analysis of 19 J-3s listed for sale revealed a median price of $43,900. The roughest examples were listed for around $30,000 while the finest, fully-restored examples topped out at $85,000. With comparable types starting out at $20,000 to $25,000, this reflects a premium of about 20 to 30 percent for the J-3. “The Cub Premium” aside, the variance in price within the type reflects the overall condition of the individual aircraft as well as the STCs and modifications in place. While a 100 percent original restoration offers value to traditionalists, more powerful engines and basic electric systems offer value to those interested in additional performance and usability.

Anecdotally, we’ve seen several examples that have been discounted by as much as $10,000 after sitting unsold for a month or two. This could be the result of some overly-optimistic initial prices, but it could also be a sign that the market is beginning to soften a bit.

Flight Characteristics

With a relatively snug cabin and a particularly tiny front seat, larger individuals may need to sacrifice some comfort to take up a Cub. In cold weather, the combination of a drafty cabin and lackluster heater can make these tight accommodations even more so as the occupants add layers of clothing. Snug-fitting, narrow-toed shoes are critical in a J-3. Bulkier footwear like boots can become caught on the cables and structural supports adjacent to the rudder pedals, and the lack of feel through thick soles can make it difficult to discern where the small heel brake pedals are located. Minimalist shoes with thin soles reward a J-3 pilot with deft freedom of movement and great feel.

Some thought is necessary for overnight trips, as well. The J-3’s baggage compartment, such as it is, provides little more space than a car’s glove box. Some owners leash bags into the front seat when flying solo, but extreme care must be taken to ensure the bag and all of its straps are perfectly secured lest something become jammed in the flight controls. The solo pilot must also ensure the altimeter is set before strapping in, as they will not be able to reach it with the belt fastened. Once settled in, the occupant of the rear seat will experience a near-total lack of forward visibility. Using S-turns on the ground and peripheral vision during takeoff and landing becomes necessary. This is all good practice, as the J-3 may only be flown solo from the back seat. One benefit to flying from the backseat is the additional feel it provides with regard to coordination. As the occupant is positioned farther away from the center of rotation, uncoordinated flight feels more pronounced and is thus more noticeable than it is from the front seat.

In airplanes that lack electrical systems, hand propping is necessary. Quality instruction from an experienced teacher pays off here, and the J-3’s relatively low engine compression enables just about anyone to do it safely and successfully. Some owners have in-stalled a starter and a battery without an alternator to ease starting while saving weight. When the battery becomes depleted after a few months of use, they simply plug it into a wall outlet to recharge it. Radios are another concern with versions that lack electrical systems. Most owners tend to install a handheld radio with an external antenna and an intercom to enable the use of headsets. These are typically battery powered, as are any iPads and any other handheld devices.

Most J-3s are able to get off the ground relatively quickly, but after becoming airborne, a 65 or 75 hp machine will provide its occupants with a rather ponderous climb rate. Hot days, high elevations, heavy passengers, and departure-end obstacles should all be carefully taken into account. In the air, the J-3 is all about fun. The upper and lower doors may be left open in flight, providing a panoramic view of the countryside below. The sparse instrument panel provides basic information without demanding attention. The open lower door also serves as a handy stall indicator—when the airplane reaches the brink of entering a stall, the lower door will flip up and flutter in the turbulent air.

In cruise, a 65 hp J-3 will sip fuel at a rate of about 4 gph while returning a cruise speed of about 70 mph. More powerful engines will burn an additional 1 to2 gph, but the added power tends to improve takeoff and climb performance more than cruise speed. A J-3 equipped with the Continental C90, for example, will leap off the runway but will only achieve about 75 mph while burning about 5.5 gph.

Flight controls are well-positioned and easy to reach. For those accustomed to flying a Luscombe or Grumman, roll control is downright lazy; the Cub feels like the aileron hinges have been overtightened and the cables replaced with rubber bands. The rudder and elevator are responsive, however, and after spending a bit of time learning the optimum blend of control inputs, the J-3 is simple and straightforward to fly. While the J-3 still runs you the risk of ground loops, it’s considered to be forgiving. The landing gear is suspended by bungee cords, and though there’s a difference between the results you get landing with fresh bungees versus aging ones, the system is quite robust and shrugs off even the firmest landings.

Ownership

On one hand, the Cub is one of the simplest certified airplanes available. But on the other hand, the airframe incorporates fabric-covered steel tubing and, depending on the model year, may also incorporate a wood wing spar. Like a violin or cello, the airplane demands care and attention, and a Cub that’s been neglected can become very expensive to bring back to life.

Owners report quotes of around $40,000 to have all of the fabric replaced on a J-3. While some of the expense goes toward addressing airframe issues that are discovered during the process, fabric replacement is lengthy and tedious. When evaluating a Cub, a wisebuyer takes the fabric’s age into account and maintains a fabric reserve to more easily absorb the cost.

For a 75-plus-year-old airplane produced in such numbers, the J-3 has few airworthiness directives (ADs). The most notable requires the periodic inspection of the wing struts and strut forks, but this AD can be eliminated by replacing those parts with modernized versions. Other ADs are either one-time or easily addressed.STCs, on the other hand, are plentiful. A wide variety of engine options exist, from the original 65 hp Continental to the 85 and 90 hp versions, as well as the 100 hp O-200. When shopping for a J-3, sticking with the J-3C version makes it easier to later switch to different engine models. It was originally equipped with a Continental engine, so an owner can install a C75, a C85, or a C90-8 with a logbook entry from their A&P. The process is far more tedious when attempting to install one of these engines on a J-3F originally equipped with a Franklin engine or a J-3L that originally came with a Lycoming.

Like any steel-tubed taildragger fuselage, a thorough pre-purchase inspection pays close attention to the lower fuselage longerons for rust or corrosion. It’s also smart to closely inspect the jackscrew that operates the elevator trim; if play is detected at the leading edge of the horizontal stabilizer, the jackscrew might require replacement. The fabric must be cut to access it.

Airframe parts are easily sourced from a number of companies, and unlike some types, the J-3’s airframe doesn’t require any parts that are particularly difficult to find. Owners report annual inspection costs of around $1,000 if no issues are found. Owners report relatively reasonable insurance premiums, as well. One 18-year-old with 150 hours of total time and only 20 hours of tailwheel time paid $1,380 for a year of coverage with a $30,000 hull value. An experienced ATP with significant tailwheel time paid about half that for the same hull value. The type club J3-Cub.com is highly regarded among owners as a place to ask and answer questions, and Clyde Smith at cubdoctor.com is considered by many to be the guru of fabric Pipers.

What a J-3 lacks in speed, capacity, and ergonomics, it makes up for in personality, simplicity, and fun. Like swinging a leg over a vintage Ducati or sliding into a Porsche 356 Speedster, the experience is sublimely raw and unrefined. The J-3 commands a premium over other types, but it holds a correspondingly higher resale value. Its simplicity makes it relatively inexpensive to own, fly, and maintain. The mix of legacy and economy is compelling, and rare’s the J-3 owner that regrets their purchase.

PIPER J-3 CUB

| Price: $30,000 to $85,000 |

| Powerplant (original): Continental C65, 65 hp |

| Normal cruise speed: 70 mph |

| Endurance: 3 hours @ 4 gph |

| Baggage capacity: 20 lbs. |

| Takeoff distance: 370 ft. |

| Landing distance: 270 ft. |

| Insurance cost: Low |

| Annual inspection expense: Low, unless fabric work is required |

| Recurring ADs: Few |

| Parts availability: Good (from type clubs and owners) |

When FLYING reported on the Piper J-3 Cub in its October 1946 issue, the U.S. was just one year out of World War II, and pilots returning to the civilian world were converting to private pilot certificates—then licenses—in droves. FLYING noted the J-3’s top speed 83 mph and range of more than 200 sm as benefits to the pilot seeking an easy trip into the sky. Thirty years later, in 1976, contributor John Olcott waxed nostalgic about the airplane: “Breathes there the pilot, with soul so dead, who never to himself hath said, ‘I want a Cub that’s Piper bred?’

“The low stalling speed and soft stall characteristics make the Super Cub an easy taildragger to land, although students seem to master landing sooner in the J-3 Cub,” Olcott went on to write. “The CG of the J-3 required pilots to solo from the rear seat, which forced them to look out the side of the Cub at precisely the angle that was best for executing a proper landing.”

The post Piper J-3 Cub’s Heritage of Simplicity, Reliability appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post Inside the Career of a Sport Pilot CFI appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>With approximately 500 hours now in his logbook, Leonard is busy teaching sport pilot students from McKnight Airport (5OI8) in Johnstown, Ohio, operating from the field’s two turf runways in a Quicksilver Sport 2S, a 1938 Taylorcraft BC-65, a 1946 Taylorcraft BC-12D, and a pair of Aeroprakt A22 LSAs. Teaching under the banner of Heavenbound Aviation, Leonard is able to reach a wide spectrum of sport pilot students as well as certificated students who desire to earn a tailwheel endorsement or receive Part 103 ultralight training.

In speaking to FLYING, Leonard makes it abundantly clear that when it comes to teaching zero-time sport aviation students, there is a long list of variables that can determine the time and cost of training for each student.

Let’s dive deep into this topic, and view the career of a sport pilot CFI, from an instructor’s perspective.

Understanding the Mission

Before the first lesson, Leonard digs into the student’s mission to determine just why they are seeking to earn their sport pilot certificate (which he calls an “SPC”). “We interview every potential student and try to establish what their aviation goals are,” Leonard said. “Being that we train in multiple different aircraft (Taylorcraft, Aeroprakt, and Quicksilver), knowing what the student's goals are is very important in determining what aircraft they train in. Also what aircraft the student wants to own/fly after they get their license is important in determining what aircraft we train them in.”

There are many things to consider before a plan to train a student is made. Leonard asks if, for example, the student plans to fly a Kitfox, a Zenith, an RV-12, or maybe a low-mass, high-drag ultralight? Do they plan to fly tailwheel or nosewheel? What avionics do they want, touchscreen and autopilot or old-school steam gauges? “Once we have figured out what their overall mission is, we ask if they just want to fly on calm evenings and enjoy the sunset, or do they want to travel and do a lot of cross-country flying? Are they going to be flying off of a 5,000-foot paved runway, or their own 600-foot farm strip with a barn at the end? We try very hard to determine the best fit for each student and train them in the way that would be most helpful in their mission. Everyone receives the same fundamental training, but once they have their basics down, we press forward with training suitable to what their mission is,” Leonard explained.

Your Cost and Time May Vary

While the FAA has set a minimum number of training hours to earn an SPC, Leonard said he sees wide variations in the actual number of hours it takes to prepare his sport students for their practical test (check ride).

“It all depends on the learning ability of the student, and how well they are able to absorb and then apply the information that is being given to them,” Leonard said. “I would say the two biggest variables to this are age and determination. If the student is a young and determined 30-year-old, they have a really good chance of completing their SPC at minimums. If the student is 60-plus, then they might have close to 50 hours to get their license.”

The training is the same for all students, Leonard said. “Typically we are going to spend the first 5 to 10 hours just on air work (ground reference maneuvers, steep turns, slow flight, and stalls) because I really want the student to know how to feel the airplane. We often will cover up the airspeed indicator on practice landings because I believe acquiring the skill of ‘flying by the seat of your pants’ can be life and death in aviation. After that, we move on to landings, and usually whatever time it takes to master the air work is about what it's going to be to master the landings. Once the student solos, we start planning their cross country and doing checkride prep.”

The frequency of lessons is, just like students earning a private ticket, a key factor in the total time it takes to pass a check ride. “The 65-year-old students that are only flying one hour a week are going to be way over the minimum hours required, while the motivated 25-year-old flying 3 to 4 hours a week has a good chance of getting it close to minimums,” Leonard said. “I would say the average is 25 to 40 hours depending how often they fly, what aircraft they fly, and how quickly they learn.”

Leonard added that the sport pilot written test can be one of the biggest inhibitors to people getting their SPC. “If a student doesn’t start their ground school until after they start flight training, they usually put it off because all they want to do is fly. If a student comes to us and they already have their written test done, usually we can get them through their SPC pretty quick. It all comes down to motivation and determination,” he said.

First Solo Flights

For any CFI, a student’s first solo can be a moment of elation or trepidation, and sometimes both. “I can feel both joy and anxiety watching my student lift off on their first solo,” Leonard said, “because it is an incredible feeling! Seeing their face when they climb out of the airplane with their big smile is truly awesome! I love being able to be the first one to shake their hand and congratulate them on their solo. Being able to share a passion that I love so much, and seeing it become their passion after their solo, makes all the heart-thumping rough landings worth it!”

Leonard knows that these first solo flights can sometimes lead to great things, far beyond just enjoying the privileges of an SPC. “We have had a few students that went on to much more advanced ratings and certificates,” Leonard said. “One of our newest started training while he was in high school, and is currently at Bowling Green University in Ohio enrolled in the aviation program with plans to go on to commercial, CFII, and hopefully onto a charter operation. Another recent student is now enlisted in the U.S. Naval Academy and is hoping to fly fighter jets.”

As a man of faith, Leonard’s career as a sport CFI is closely related to his missionary work in South America.

“I never try to push my faith in Jesus on anyone, but when my students ask how or why I got into aviation, it brings up the conversation of my faith,” he said. “You get to know someone pretty well when you are in a small plane together for 20-plus hours.”

The post Inside the Career of a Sport Pilot CFI appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>The post The Piper Tomahawk: A Lot More Airplane for a Lot Less Money appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

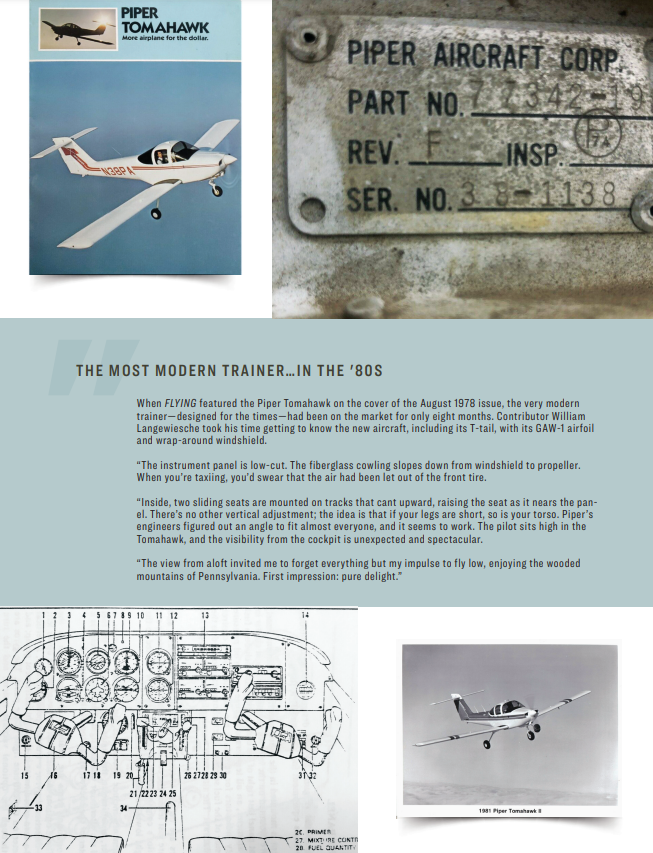

]]>But what if one type’s perceived weakness is some-thing that can be addressed with awareness and ap-propriate training? In the case of the Piper PA-38Tomahawk, its unique stall and spin characteristics resulted in accidents and a poor reputation early in its production run. The reputation lingers today, but owners agree that if one is willing to train and fly appropriately, it becomes a non-issue—and a non-issue that enables a prospective owner to obtain a lot more air-plane for a lot less money than other types.

Design

Back in the late 1970s, the field of training aircraft was dominated by legacy types that traced their designs back to the 1930s and 1940s. The popular Cessna 150and 152 were based upon the old 140, Cubs and Aeroncas had changed little over the years, and—whether equipped with a nosewheel or a tailwheel—most trainers also had high wings, cramped cockpits, and limited visibility.

When Piper set out to claim market share from Cessna in the primary trainer category, it took a fresh approach. Rather than build an updated Cub or a smaller Cherokee, Piper surveyed thousands of flight instructors across the country to determine what characteristics were most desired in a training aircraft. It solicited input on what features the perfect one should have and how it should fly. The instructors provided plenty of input.

Having spent decades in cramped cabins, they asked for more space and comfort. Having dealt with huge blind spots in the form of a high wing positioned at eyelevel, they asked for more visibility. And they wanted an airplane with a sharper, more pronounced entry into stalls and spins. They reasoned that a student cannot fully understand or properly learn spin recovery in an airplane that will automatically return to normal flight when the controls are released.

Piper got to work and created an airplane that me teach of these demands in the form of the Tomahawk. It built the airframe around the popular 112 hp, four-cylinder Lycoming O-235. Although the low-wing de-sign necessitated a fuel pump, Piper positioned the fuel selector in a location on the panel that’s both easy to see and easy to reach. And, like so many other models in that era, they opted for the style of a T-tail.

Model History

The result of the research was a new training air-craft that was thoroughly modernized and differentiated from the legacy trainers of the day. In the end, Piper would sell nearly 2,500 examples between 1978and 1982.In those four years of production, the Tomahawk line remained simple and uncomplicated. The vast majority of Tomahawks are the initial model, known simply as the PA-38 Tomahawk. During the last two years of production, Piper introduced the Tomahawk II variant, with minor improvements to the cabin: heating, ventilation, and soundproofing. The company also made a few smaller improvements to the interior to provide more comfort to those on board.

Market Snapshot

A survey of Tomahawks listed for sale at the time of this writing found eight examples ranging in price from $25,000 for a particularly rough example to $69,000 for one with a freshly overhauled engine and updated avionics. The median price of the group was $30,500, and the median airframe time was 3,717 hours. A total of 444 Tomahawks are presently listed on the FAA registry.

Because many Tomahawks have been used for flight training at busy schools, it pays to be discerning. Air-frame total time is something to note, as is the condition of an aircraft that might have led a hard life at the hands of primary students. However, an airplane that has been used regularly over the years tends to accumulate fewer issues in general than one that has been a hangar queen, so don’t discount a former school model.

Flight Characteristics

The Tomahawk’s T-tail makes it easy to spot from across a ramp. Like the T-tails Piper fitted to the Arrow IV and Lance, it is said to have been chosen by the marketing department for its looks, but it has more drawbacks than legitimate performance advantages. A Tomahawk pilot must retrieve a ladder to perform a thorough preflight inspection, and to clear ice and snow off of the horizontal stabilizer in the winter or remove bugs from the leading edges in the summer.

Fortunately, the Tomahawk’s other design elements offer legitimate benefits that are immediately apparent. If the cabin size and layout of the Tomahawk had been the accepted norm and the competition had all waited until the late 1970s to introduce their cramped cabins with limited visibility, their airplanes might not have done so well in the marketplace. Indeed, the Tomahawk’s roomier cabin feels downright luxurious compared to an early taildragger or Cessna 150, and the outstanding visibility comes as a pleasant shock to everyone except possibly Ercoupe pilots.

Most two-place trainers endowed with engines in the 100-hp range require discipline with regard to loading, and the Tomahawk is no exception. With full fuel, anyone much over 150 pounds would be wise to consider the weight of the other occupant before de-parting—a survey of 18 owners found that the aver-age full-fuel payload was 303 pounds. Fortunately, the 30-gallon fuel capacity is larger than that of many competing models, and this provides some flexibility with regard to payload.

After settling in, a Tomahawk pilot will find that most controls are well-designed ergonomically, botheasy to see and reach. Taxiing is straightforward and the nosewheel steering is positive and responsive.

A pilot unfamiliar with a T-tail would be wise to re-view its nuances prior to flight. Because the horizontal stabilizer and elevator are positioned outside the propeller slipstream, the elevator takes more time to be-come effective, and thus, a bit more time and distance is required to raise the nosewheel for a soft-field takeoff.

If the pilot continues to hold full nose-up elevator as the nose rises, they might be startled when the horizontal stabilizer enters the slipstream, instantly gains effectiveness, and sends the nose abruptly upward. This stems from the T-tail design itself, rather than representing a safety issue specific to the Tomahawk, and it’s easily countered after the pilot becomes familiar with the tendencies of the T-tail.

The rest of the takeoff and climb out are typical of any O-235-equipped trainer, predictable and a bit ane-mic when fully loaded. The spring-based elevator trim and the tiny trim wheel feel less effective and less precise than trim-tab based designs, but they do the job.

Most owners report cruise speeds in the 95-knot range with a fuel burn of roughly six gallons per hour. No Tomahawk review would be complete without mention of the airplane’s stall and spin characteristics. The topic of much debate over the decades, many studies and analyses have been conducted, and opinions still differ. People who have never flown them equate them to death traps, predisposed to enter and difficult to recover from spins.

Those who fly the Tomahawk understand that when designing the airplane, Piper simply gave the afore-mentioned group of CFIs precisely what they wanted—an airplane more willing to enter stalls and spins, and one that requires specific inputs to recover from them. That said, there is still debate regarding the consistency of the airplane’s stall and spin characteristics.

Master CFI Rich Stowell, who has flown more than 26,000 spins in more than 160 different airplanes, tested one Tomahawk in depth. He found that its spin characteristics were unremarkable compared with other airplanes and that the airplane performed as Piper literature states it should perform. Stowell does, however, go on to question whether the spin characteristics are truly uniform across the fleet.

The National Transportation Safety Board raised the matter of Tomahawk stall-spin characteristics formally in a Safety Recommendation to the FAA in 1997 and asked that the agency conduct an investigation and test flights. The FAA did so, and it reported in 1998 that the concerns were unsubstantiated.

In any case, owners strongly recommend seeking thorough flight instruction from an instructor who is well versed in the Tomahawk. If doubts remain about the stall/spin characteristics of a particular Toma-hawk, it shouldn’t be difficult to find a qualified instructor or aerobatic pilot to go spin the airplane and report on its characteristics.

In normal cruise flight, the Tomahawk is an enjoy-able airplane to fly. The sweeping, unrestricted visibility makes it easy to spot other traffic; it handles predictably, and the heater keeps the cabin toasty—even on frigid winter days in northern climates.

On approach, the airplane flies predictably, and the pilot can readily make changes to airspeed or profile. One mustn’t forget that T-tail during landing, how-ever—leaving some power in or landing at a higher-than-usual pitch attitude can catch a new Tomahawk pilot off guard. As on takeoff, if the horizontal stab sinks low enough to enter the propwash, effectiveness spikes and the pitch can increase abruptly. The effect is not unlike encountering a sudden wind gust. While recovery is easy and straightforward, it’s a nuance for which one should be prepared.

Ownership

Economy is one of the primary strengths of the Tomahawk. A relatively low purchase price, a 2,400 hour engine TBO, and low fuel burn keep operating costs at a minimum. Insurance is also relatively affordable. Multiple low-time owners report annual insurance premiums between $1,000 and $1,500 per year, even for new student pilots utilizing the Tomahawk for their primary flight training.

The relatively simple airframe is straightforward to repair and maintain, and lacks complicated, proprietary components that can make other types more challenging to service. With nearly 2,500 examples produced, the supply of replacement parts helps to keep Tomahawks airworthy and out of the maintenance hangar. Prospective owners are wise to care-fully review the maintenance logs of any Tomahawk they find. Not long after the type entered production, a high number of stall/spin accidents resulted in the FAA creating an airworthiness directive (AD) that requires the installation of four stall strips on the leading edge of the wing. Accordingly, every Tomahawk should have had them installed.

Other ADs introduced a life limit for certain parts. Every 3,000 hours, the vertical stabilizer attachment plate must be replaced. The part isn’t expensive but the job requires about 40 hours of labor.

The Tomahawk wing is subject to a life limit of 11,000 hours. Although this is a high number, many Toma-hawks have led a busy life of flight instruction and have correspondingly high-time air-frames. Fortunately, Sterling Aviation Technologies of Goodyear, Arizona, offers a kit that extends the spar life to at least 18,650 hours. The $4,300 kit requires approximately 64 hours of labor to install, and it’s a great alter-native to scrapping a high-time airframe.

Other ADs apply, but none require an inordinate amount of time or money to address. The majority are either one-time mods or can be resolved readily.

Few STCs are offered for the Tomahawk and thus, most Tomahawks are virtually identical from a mechanical standpoint. One STC allows for the installation of higher-compression pistons, bringing the horse-power from 112 to 125. Although the increase in power is modest, it is said to be quite noticeable. Unfortunately, the STC seems to have become orphaned and is no longer available for purchase/installa-tion on existing Tomahawks

.Although no official type group presently exists, the “Piper Tomahawk Owners” Facebook group is vibrant and full of enthusiastic owners who are eager to welcome newcomers into the fold. More information can be gleaned through the Piper Flyer Association.

Now more than ever, it has be-come difficult to find a certified, 1980s-vintage airplane in the $30,000 to $35,000 range. The Tomahawk offers relatively easy, straightforward ownership, and existing owners take every opportunity to praise their machines and recommend the type to others.

Piper Tomahawk: By the Numbers

| Price | $25,000 to $69,000 |

| Powerplant (varies) | Lycoming O-235 |

| Max cruise speed | 108 kias |

| Endurance | 5 hours at 6 gph |

| Max useful load | 505 lbs. |

| Takeoff distance over a 50-foot obstacle | 1,440 feet |

| Landing distance over a 50-foot obstacle | 1,462 feet |

| Insurance cost | Low |

| Annual inspection expense | Low |

| Recurring ADs | A couple to watch for |

| Parts availability | Good (from the OEM and others) |

The post The Piper Tomahawk: A Lot More Airplane for a Lot Less Money appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>