The post Air Compare: Meyers 200 vs. Navion appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>Among various aircraft models, some are the equivalent of basic condominiums. Nothing fancy, reasonably common, and generally straightforward to own and live in with few headaches or surprises. A Cessna 172 and Piper Cherokee would fall into this category nicely, serving as fantastic first airplanes that are easy to own, fly, and maintain.

But many people eventually outgrow their starter homes and want more out of house ownership. A garden, perhaps, or possibly a pool. Maybe some more square footage and garage space. A home that demands more attention and upkeep but one that also provides a richer, more in-depth ownership experience.

Similar opportunities abound to take airplane ownership to the next level, and the two types featured here do so in their own unique ways. The Navion, with its 1940s-era lineage and systems that bear more similarity to a T-6 Texan than a 172, demands more knowledge and attention than the simplest types, but its unique military background and extensive community of friendly, dedicated owners make it a type with which few will ever become bored.

Similarly, the rarity of the Meyers 200 demands that each owner becomes something of an aeronautical curator. With around 125 examples built and only 78 remaining on the FAA registry, an owner must sharpen their sleuthing skills and network to source certain parts and experienced maintenance. The flying techniques, mechanical nuances, and subtle design features are not an instant Google search away. But support among Meyers owners is passionate and generous, and newcomers are enthusiastically welcomed into the tightly knit fold.

Here, we explore each type and compare what it offers owners beyond the basic performance specs.

Design and Evolution

From the outside and from a distance, the Meyers and Navion appear somewhat similar. Both are low-wing, retractable-gear singles. Both emit the growl of 6-cylinder engines, primarily 200 to 285 hp Continentals. And both provide their occupants with panoramic visibility out of an array of windows. But approach them for an up-close look, and significant differences become apparent.

On the ramp, the Navion stands taller than any single-engine, low-wing piston this side of a Mooney Mustang. More than a foot taller than the Meyers and more than 3 feet longer in both length and span, the Navion is a massive, truck-like machine with a cabin volume that follows suit. For pilots who appreciate roominess in a cabin or simply enjoy the feel of flying a large, substantial aircraft, few single-engine piston options top the Navion.

The Meyers is a compact, svelte machine by comparison. But a glance at the specs reveals some hidden surprises. Despite the smaller size, its empty weight is nearly identical to the larger Navion, but with 22.5 fewer square feet of wing area, the numbers hint at the higher-speed capability of the Meyers. Per each company’s data, the smaller Meyers has an inch more cabin width than the Navion—another indication that one of these types abandoned ease of production in favor of meticulous engineering.

The Meyers 200 was certified in 1958 and saw small, methodical improvements through the course of its production run, which came to an end in 1967. The first production model was the 200—only two examples were built, and they were both equipped with the 240 hp Continental O-470M engine. The 200A replaced the 200, and the change upgraded the engine to the 260 hp IO-470D.

In 1961 came the introduction of the Meyers 200B, which had an improved panel layout as well as a higher structural cruising speed and redline. This was replaced by the 200C, which incorporated a taller passenger cabin and larger windshield. The 200D was the final model with a 285 hp IO-520 and a flush-riveted wing. Together, these enhancements produced a notable improvement in speed to the tune of 210 mph at 7,500 feet and 75 percent power.

Partway through the production run of the 200D, Aero Commander purchased the type certificate and tooling and continued building the airplane as an Aero Commander 200D in its plant in Albany, Georgia. Later, the Interceptor Corp. purchased the type and marketed the airplane under that name but never sold any examples. Because both Meyers and Aero Commander produced the 200, however, it’s important to search for classified listings under both manufacturers so no options stay hidden and unnoticed.

Similarly, between 1946 and 1962 the Navion was manufactured by a number of different OEMs, all of which should be searched for when shopping for one of your own. Initially built by North American Aviation in the 1940s, the Navion was later constructed and sold by the Ryan Aeronautical Co., and finally, the Navion Aircraft Co. and Navion Aircraft Corp.

By the time production ended, more than 2,600 examples of the aircraft had been produced. Toward the end of the run, the Navion Rangemaster appeared with tip tanks and a traditional roof incorporating one left-side door.

The Navion was not built specifically for the military, and while all military L-17s are Navions, not all Navions are L-17s. Nevertheless, the overall design incorporated a number of systems and features the military found appealing. The hydraulic system which powers the gear and flaps, for example, was easily understood and maintained by service members. Additionally, the robust airframe and landing gear designs were well suited to the unimproved landing areas that military Navions would visit in their liaison role.

Conversely, while various design aspects of the Meyers also emphasized durability and robustness, the airplane was more comparable to a coachbuilt luxury car than a Jeep. Although it incorporated features such as a chrome-moly steel cage wrapped around the passenger cabin, the overall design is more complex and would prove decidedly more time-consuming to manufacture than the utilitarian Navion.

Market Snapshot

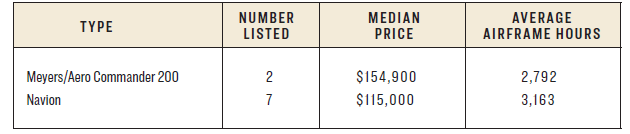

Other than price, useful load can be the most notable difference between the two. Given the relative rarity of each type, it’s perhaps not surprising the sample size of the examples available on the open market follows suit. In our survey, we were only able to find two Meyers and seven Navions listed for sale. Like other types, the value of each has climbed significantly in the past few years, and the difference in value between the two types corresponds with the consensus among owners that the Meyers tends to be the pricier of the two.

An analysis of the FAA registry reveals that while the number of actively registered examples has naturally and predictably decreased among both types, a higher percentage of Meyers aircraft remain. Of the 125 examples built, 78 (62 percent) are still active on the registry. In comparison, only 33 percent (858) of the 2,634 Navions built remain in the database. The reasoning behind this is unclear, but it’s possible the rarity of the Meyers motivates owners to repair badly damaged 200s and return them to service rather than part them out.

Whether shopping for a Meyers or Navion, a prospective buyer would be wise to engage with the owners’ group to inquire about unlisted examples and possibly connect with current owners beginning to entertain the idea of selling. In addition to benefiting from sneaking into line ahead of other buyers, an airplane owned by an active member of that type’s owners’ group will likely have been better cared for than one possessed by an inactive, uninvolved owner or estate.

Flight Characteristics

One of the most significant differences between the Navion and Meyers becomes apparent during the boarding process. With the exception of the later Navion Rangemasters that incorporated a traditional roof and left-side cabin door, all standard Navions have a large canopy that slides back on rails to provide access to the entire cabin. Not unlike a Grumman AA-5, you step from the wing into the cabin and lower yourself directly down into the seat.

The Navion’s canopy exhibits pros and cons. On the one hand, the ability to completely open it makes it very easy to access the front or rear seats and similarly smooth to load oversized baggage. Opening the canopy on a hot day during taxi provides a refreshing blast of air through the entire cabin—and it can even be opened in flight.

A downside to the canopy is the challenge it presents concerning the installation of shoulder harnesses. With no fixed overhead anchor points to attach them, most owners fly their Navions with only lap belts. Some install lap belts with integrated airbags for an additional layer of safety, and a few have installed custom-built frames behind each front seat that provide a place to mount shoulder harness anchors. But while there are solutions, it’s a concern with which the Meyers and Rangemasters, with their traditional doors and roof, need not contend.

Settling into the Navion, it’s easy to appreciate the vast amount of space in general and shoulder/headroom in particular afforded by the larger airframe. While various sources list actual cabin widths to be roughly within one inch of each other, the Navion feels notably more roomy at and above shoulder height, particularly compared to pre-D-model Meyers 200s. Navion owners report this space is greatly appreciated by their passengers, who are able to freely move between the front and back seats on longer flights.

In flight, the Navion is far slower than the Meyers in cruise, but its large flaps provide a 12 knot lower stall speed and fantastic low-speed handling qualities that make it comfortable to negotiate on short strips. Using the IO-520 as a baseline, the Meyers will cruise at roughly 180 knots compared to 145 to 150 knots in the Navion. As both will burn the same 13.5 gallons per hour in cruise, the Meyers becomes noticeably more economical to fly as the planned distances increase.

Both types exhibit fantastic handling characteristics, with the Meyers having a slight edge by virtue of torque tubes and pushrods in lieu of control cables. Both provide excellent, stable instrument platforms, and both have successfully welcomed new low-time private pilots to the ranks without issue. One owner who earned their private pilot certificate in a 172 and bought a Navion with 90 hours of total time reported feeling comfortable in it after around 10 hours of dual.

Although neither type possesses any unique pitfalls or traps into which unsuspecting newcomers might fall during initial training, it is advisable to locate an instructor intimately familiar with the type for transition training. Instructors can be found in each respective type group. Several have been formed, such as the American Navion Society (ANS, navionsociety.org) and the Meyers Aircraft Owners Association (MAOA, meyersaircraft.org). The cost of airfare and lodging to bring a qualified instructor to your location is regarded as money well invested.

Ownership

Both the Navion and Meyers are unique enough to warrant a special effort for a high-quality, thorough prepurchase inspection. When arranging one, it is desirable to proactively join the type group for the object of your interest— MAOA or ANS. For a nominal membership fee, one can engage with the group and become connected with qualified mechanics who are intimately familiar with the intricacies of each respective type.

In the world of Navion, owners commonly mention two specific pieces of advice. They point out that because of the wide range of subtypes and selection of supplemental type certificates available for the airframe, no two Navions are alike. Additionally, they caution against purchasing certain engine/propeller combinations.

With regard to the less-desirable engines and propellers, the concern is less with the components themselves but rather the availability of parts and service. The geared Lycomings, such as the GO-435 and GO-480, for example, are not well supported by the manufacturer, and the number of engine shops that will even consider performing overhauls on them is dwindling. Similarly, replacing the rare, splined Hartzell propeller fitted to certain engines can be cost prohibitive. Owners advise spending more upfront to acquire a Navion with a more easily serviceable engine and prop rather than deal with such headaches down the road.

While Navion owners report no onerous or burdensome recurring airworthiness directives (ADs) with which to contend, the Meyers boasts an airframe with zero airworthiness directives since introduction—a claim not commonly seen among comparable types. When shopping for a Meyers, the limited production numbers do not allow a prospective owner to become choosy, but fortunately, there are no subtypes or modifications regarded as ones to avoid. If one has the luxury of multiple examples from which to choose, three primary factors come into play—general condition, engine horsepower, and the taller passenger cabin of the 200D.

Corrosion is far less of a problem for the two types than others of the era. In the case of the Meyers and earlier Navions, each manufacturer enthusiastically slathered the airframes in alodyne and zinc chromate to protect the metal. Later Navion manufacturers were less generous with the protectants, but nevertheless, corrosion issues typically don’t haunt either airframe.

With both types, it’s critical to buy from an owner who has willingly spent money on preventative maintenance rather than deferring it. Just as ignoring a few missing shingles on a house’s roof can result in structural rot and expensive repairs, deferring repairs on a Meyers or Navion can easily lead to costly, substantial work in the future. An owner with a spotless, meticulously organized hangar and detailed expense records will likely have been a good caretaker of the airplane they’re selling.

Insurance cost is a concern with both types. While owners with substantial time in the models report figures as low as $2,500 at typical hull values, new pilots with little time in type can see quotes as high as $7,000 to $10,000 per year. Some only carry liability insurance, keeping their premiums to $1,000 a year or less. It would be wise to shop around and learn how many hours in type various insurance providers would require to lower their premiums before committing to either type.

Our Take

Like many aircraft comparisons, evaluating the Navion and Meyers head-to-head becomes less a matter of crowning a winner and more about matching the strengths of each to one’s particular preferences.

The Navion is a larger airplane that was optimized for mass production and incorporated robust engineering and systems that were well suited for military use. The owner community is extensive and vibrant, with regular events and fantastic support. The Navion’s military lineage remains strong, with owners conducting regular formation flying clinics and group fly-ins. In today’s market, most Navions can be had for tens of thousands of dollars less than an otherwise comparable Meyers.

The Meyers was designed with the singular goal of achieving fantastic speed and performance with little to no consideration given to simplicity or ease of production. Owners appreciate the steel cage that surrounds the passenger cabin as well as the blistering cruise speed and cross-country capability that make the Meyers the single-engine piston equivalent of a private jet. Although the Meyers community is far smaller than that of the Navion, owners are supportive and happily make resources available to one another, up to and including the original jigs and tooling, in the event an unavailable major airframe part is required.

Beyond the technical strengths and specifications, the less-tangible aspects of the ownership experience differ significantly as well. For an owner interested in the military ancestry of the Navion, that type will provide an entire layer of ownership experience that many other types lack. From the robust metal switchgear to the potential service history of an authentic L-17, these elements are entirely legitimate despite not being quantifiable on a spec sheet.

Similarly, the Meyers offers an ownership experience that might appeal to a sentimental type. An amateur curator of aviation history would relish the opportunity to become a historical caretaker of a rare aircraft type. Similarly, someone with a deep appreciation for careful, methodical engineering would enjoy the intricacies that lie beneath the skin of the Meyers.

Regardless, both options are well loved in their respective circles. For a pilot looking to move up from a more basic, entry-level aircraft into something that presents a greater depth of rewards and challenges, both the Navion and Meyers are likely to provide one’s heart with a long-term home.

Handwrought and Homespun as Quilting…

When FLYING associate editor James Gilbert flew the Meyers 200 for a pilot report in March 1965, he recognized straightaway its purpose: “Know how some airplanes give their game away at a glance? The Meyers 200 is one of these, with its intention written all over it: to go like a bomb.” Yet Gilbert also gave a nod to the handbuilt heritage of the Meyers OTW biplane from which it was born [as well as the Meyers 145 shown below]. Still, it made for “a dastardly attack on the villain drag.”

Conversely, the Navion came to be admired by our editors for its “likable, lumbering ” style, as reported in the May 1973 issue of FLYING. Peter Garrison wrote, “It may have lost out to the [Beech] Bonanza’s speed, but today, a Navion is sought after by people who value good flying manners above sheer velocity.”

This feature first appeared in the October 2023/Issue 942 of FLYING’s print edition.

The post Air Compare: Meyers 200 vs. Navion appeared first on FLYING Magazine.

]]>